“Thermal issues are currently one of the biggest bottlenecks that are plaguing any kind of microelectronics,” says team lead Srabanti Chowdhury, professor of electrical engineering at Stanford University. “We asked ourselves, ‘Can we perform device cooling at the very material level without paying a penalty in electrical performance?’”

Indeed, they could. The engineers grew a heat-wicking diamond layer right on top of individual transistors—their hottest points—as well as on their sides. Heat flowed through the diamond to a heat sink on the back of the device. With this technique, the researchers achieved temperatures 100 degrees Celsius lower without any degradation of the device’s electrical properties. They will report their findings in San Francisco at the IEEE International Electron Device Meeting in December.

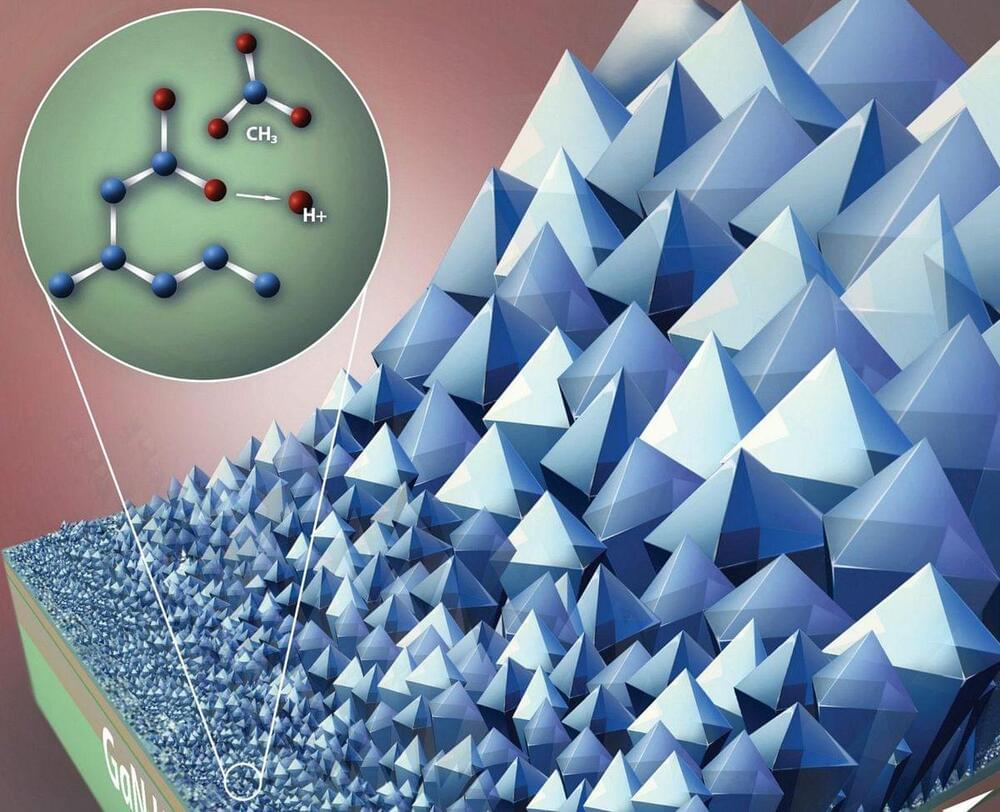

They demonstrated their technique on gallium nitride (GaN) high-electron-mobility transistors, or HEMTs. GaN is the go-to alternative to silicon for high-frequency applications, as it can sustain higher electric fields and responds more quickly to electric field changes. GaN also breaks down at a higher temperature than silicon. But not high enough: “If you go by the physics of the material, you see what its potential is, and we’re nowhere close to that today,” says Chowdhury. Keeping GaN HEMTs cool as devices shrink and frequencies grow will allow them to live up to their physics-promised potential.

Leave a reply